In my experience as a software engineer, I think it's still way to common to see production-ready code being shipped without having been profiled at least once. With the current computing power and the ever increasing number of available cores per machine, it feels like a lot of preference is generally given to readable and maintainable code at the cost of those extra microseconds. Whilst this might make sense for extremely complex code-bases in low-level languages, this is perhaps more of an issue with technologies like Python, where in general you can still make some substantial optimisations while still retaining readability and maintainability.

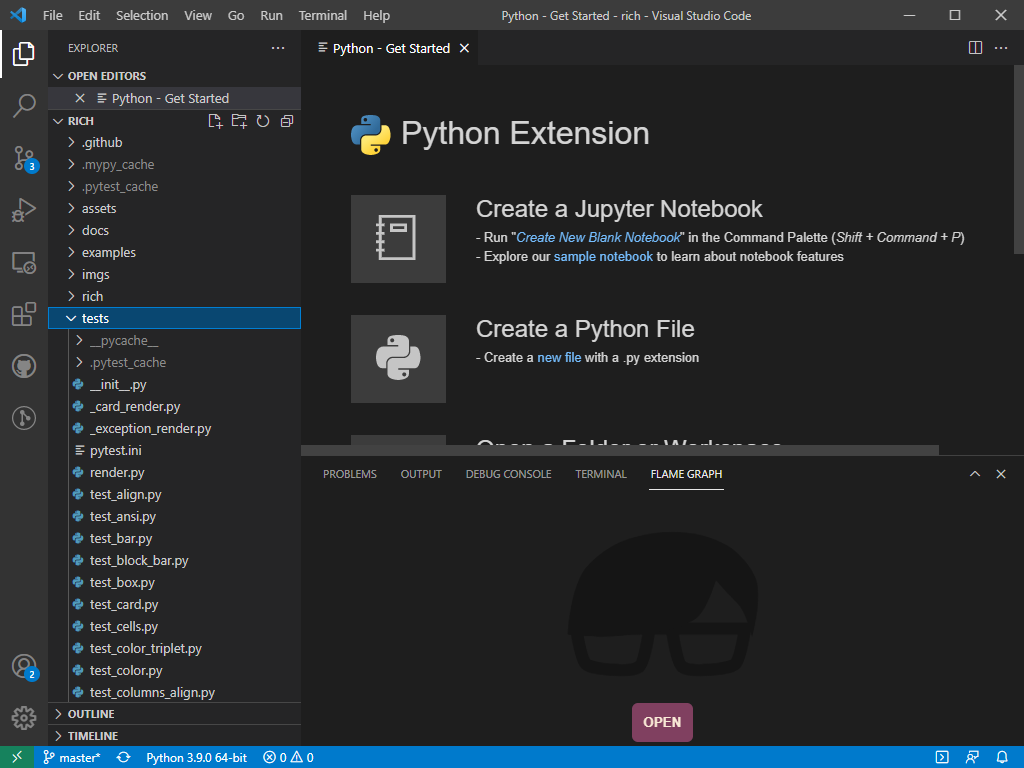

To further prove to myself that profiling is still an important step in the development process that gets overlooked, I did the following experiment. I grabbed a Python project at random, the first one that popped up on my GitHub feed, looked at its test suite and profiled the test runs. The day I did this, Rich was sitting at the top of my GitHub feed, so what follows is a trace-back of the steps that led me to contribute this performance PR to the project. Besides Python, the other tools that I have used are Austin 3 and VS Code with the Austin extension installed.

So first of all, let's make sure that our test environment is fully set up. If you want to follow along, make sure that you have Austin and VS Code installed. I was using Windows the day I made this experiment, so I had Austin installed with choco, and the VS Code extension installed from the Visual Studio Marketplace. Let's get our hands on some code now by cloning Rich and checking out that commit that was master for me at that time. Open up a terminal and type

git clone https://github.com/willmcgugan/rich.git

git checkout ce4f18c

The project uses poetry so running the test suite is as easy as invoking

poetry install

poetry run python -m pytest

Once we are sure that all the tests pass we are ready to start getting some

profiling data to see what's actually running. Version 3 of Austin comes with a

reworked sleepless mode that can be used to get an estimate of CPU time

instead of wall time. One big advantage of using a tool like Austin is that we

do not have to make any changes to the code in order to get profiling data out

of it. Besides, Austin runs out-of-process, which means that it won't have any

effects on the code. Getting profiling data is as easy as invoking Austin just

before the test run

poetry run austin -so profile_master.austin python -m pytest -vv tests

WARNING Here we can let Austin sample the whole

pytestrun because we have checked beforehand that it only takes a few seconds to complete. DO NOT try the same exact thing with long-running test suites or you would end up with a massive sample file that would be hard to process. In such cases you can either select a few tests, or run Austin with the-x,--exposureoption to limit sampling to just a few seconds, and adjust the sampling interval with the-i\--intervaloption as best suited.

The -s option turns the sleepless mode on, which gives us only the on-CPU

samples, whereas the -o option specifies the output file. Once the test run

terminates, our profiling data will be in profile_master.austin, ready to be

analysed with the Austin VS Code extension. We get the best experience if we

start VS Code from within the project's root directory as this allows us to

browse the code while we look at the flame graph. So fire up VS Code from the

terminal with

code .

and activate the Austin extension by clicking on the FLAME GRAPH tab in the

bottom panel. Sometimes you would have to right click inside the panel and click

the menu entry to fully activate the extension.

At this point we are ready to load the profiling data that we have collected.

Click on the OPEN button or press CTRL + SHIFT +

A to bring up the open dialog and select profile_master.austin. The

Austin VS Code extension will analyse all the collected sample and generate the

flame graph.

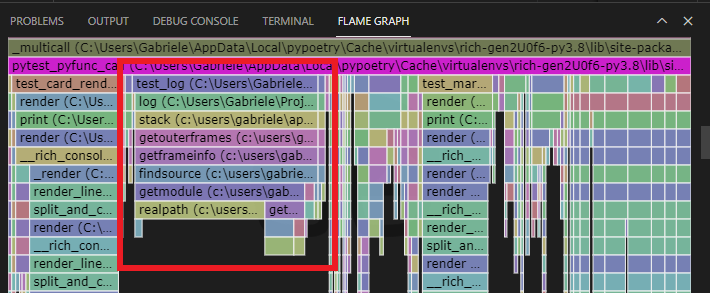

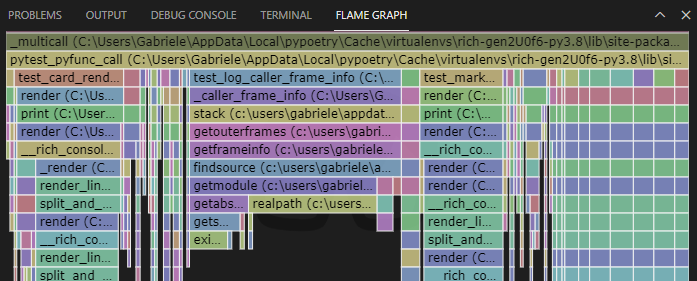

The picture we get is certainly overwhelming at first, especially for those that

are not familiar with how pytest works internally. This is perhaps a nice way

to actually find out how pytest collects and run tests. By poking around we

discover that some of the test runs are under the pytest_pyfunc_call frame. If

you are struggling to find it, press F inside the flame graph to

reveal the search input box, type pytest_pyfunc_call and hit ENTER.

The frames that match the search string will be highlighted in purple. Let's

scroll until we find the largest one. When we click on it, it will expand to the

full width of the panel to give us a better idea of what lies underneath it, and

the corresponding portion of the source code will also appear in VS Code!

We now have a better view of the tests that are being executed under this path. At this point we can start looking for the largest leaf frames and see if we can make any sense of them. When I first looked at this graph, one thing that quickly caught my eye was this particular stack.

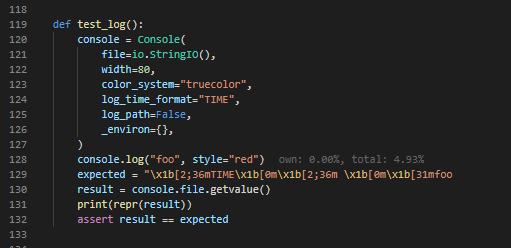

Clicking on the test_log frame reveals the test code in VS Code. Surprisingly,

the test has just a single call to Console.log, and the percent timing

annotation generated by the Austin extension tell us that, of the whole on-CPU

time for the test suite, about 4.9% is spent on that single call!

Looking back at the flame graph, we realise that all the time in the log frame

is spent calling stack. Clicking on the log frame reveals the source code

for the Console.log method and we can inspect how the information from the

stack is used to generate the log entry. The line we are interested in is 1685,

where we have

caller = inspect.stack()[_stack_offset]

So inspect.stack() is called, which according to the flame graph does a lot of

resolutions for each frame (see those calls to findsource, getmodule

etc...), none of which seems to be used in Console.log, and besides we just

pick one of the frames close to the top of the stack and chuck the rest away.

That's pretty expensive for a simple log call. Since I had some familiarity with

the inspect module with my

work on Austin and other stuff, I knew there is (at least for CPython) the lower

level method

currentframe

that would give you essential information about the currently executing frame.

From there you can navigate down the stack and stop at the frame of interest. In

this case we just need to take the parent frame of the current one, and we

already find all the information needed by the Console.log method. I made the

changes as part of the already mentioned PR

#1253, so if you check that

code out and re-run the tests with

poetry run austin -so profile_pr.austin python -m pytest -vv tests

and open the new profiling data in profile_pr.austin you will see that the

test case test_log has pretty much disappeared as it basically takes almost

zero CPU time now.

Instead we see test_log_caller_frame_info, which is the test case for the

compatibility utility for those Python implementations that do not implement

currentframe. But with CPython, calling Console.log is now inexpensive

compared to the original implementation.

See how easy it's been to find a performance issue. With the right tool we didn't have to add any instrumentation to the code, especially in one we probably had no familiarity with. In many cases you only understand your code truly if you see it in action. So no more excuses for not profiling your code before you ship it! ;P