Introduction

Due to the increasing popularity of the sample tools that were included with earlier versions of Austin, I have decided to move them into their own dedicated repositories. The TUI, for example, can now be found at Austin TUI.

Being, as I said, sample tools, the original coding wasn't very pleasant as the

main focus was on how to embed Austin into your application, rather than the

application itself. So the first step was to come up with a good design so that

the code would be tidy and easy to maintain. Austin TUI has also been my very

first attempt at a serious TUI application. The standard approach in Python is

with the curses module, but one

thing that you learn quite quickly is that such a low-level API tends to make

for untidy-looking code pretty easily if you're not careful. There are some way

out of this, in the form of higher level frameworks which offer you many cool

features and abstractions like widgets. None of them, as nice as they are,

were to my taste though.

My previous experiences with UI have almost always revolved around the notion of resource files. That is, the various bits of the user interface, like the main window, configuration and about dialogs, were all described by some DSL living in the project folder as resource files. You can take Glade as an example, which is also the tool that inspired the solution that I ended up developing and adopting for Austin TUI. With Glade, a GTK UI is described by an XML document, which is then parsed at runtime to produce the actual UI. What I wanted for Austin TUI was something similar so that I could de-clutter the Python code from all the UI definition logic, and focus only on the other aspects of a UI project, like event handling. I also wanted something that played nicely with the MVC design pattern and, as we shall see briefly, the main concept behind Austin TUI is indeed that of a view.

The View Object

The central object of the Austin TUI is the View object. This is responsible

for refreshing the interface as well as exposing the event handlers for events

like key presses. The view itself is not the UI though, but it contains a

reference to it via the root_widget. The novelty in Austin TUI is that we want

to partially build a view, or at least the UI part, using a resource file.

So take a look at the following minimalist example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?>

<aui:MinimalView xmlns:aui="http://austin.p403n1x87.com/ui" name="minimal_view">

<aui:Window name="main">

<aui:Label name="label"

text="Hello World"

align="center" />

</aui:Window>

<!-- Signal mappings -->

<aui:signal key="q" handler="on_quit" />

</aui:MinimalView>

|

minimal-view.xml

The above XML document describes a view with two main components: a Window

element, which provides the root node for the UI, and a signal to bind the

method on_quit to the key q. The UI itself contains a single label that will

display the text Hello World. When we run an application that uses this UI, we

expect to see the text Hello World centred on the screen and we also expect to

exit as soon as we press Q.

So what do we need to make the above UI work? With the framework included in

Austin TUI, all that we need to do is declare a subclass of View with the same

name as the root node of the XML document, that is MinimalView in this case,

and then build the actual view object using the ViewBuilder class, like so

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | import asyncio

from austin_tui.view import View, ViewBuilder

class MinimalView(View):

def on_quit(self, data=None):

raise KeyboardInterrupt("quit signal")

def main():

with open("minimal-view.xml") as view_stream:

view = ViewBuilder.from_stream(view_stream)

view.open()

try:

asyncio.get_event_loop().run_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

view.close()

print("Bye!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

This is all the Python code required to build a minimalist TUI that displays a

label on the screen and that quits whenever the user presses Q. Things we

notice from this example are

- we are using

asyncioto handle user events on the UI; this means that we can schedule our own asynchronous task without making the UI unresponsive; - we use the static method

from_streamof theViewBuilderclass to build a UI from file; if the file resided inside a Python module we could have used thefrom_resourcestatic method instead for convenience; - we call the

openmethod on the view object to display the UI; - we call the

closemethod on the view object to close the UI and restore the terminal to its original status.

In this particular example, we make the on_quit event handler simulate a

keyboard interrupt and we handle KeyboardInterrupt to quit nicely.

The Widgets

Austin TUI uses the widget abstraction too. Elements like Window and Label

that we have seen above are all exposed by the Austin TUI library via the

austin_tui.widgets.catalog sub-module. A window is a simple logical container

that can hold a single child, spanning the full content of the window. In the

example above, the only child of the window is the Label widget identified by

the name label. If you want to add multiple children to the window, you would

want to include an intermediate Box container widget which acts as an HTML5

flex container. Let's see how we can build a simple UI for a minimalist top

utility.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 | <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?>

<aui:MiniTop xmlns:aui="http://austin.p403n1x87.com/ui" name="tui">

<aui:Window name="main">

<aui:Box name="main_box" flow="v">

<aui:Box name="overview_box" flow="h">

<aui:Label name="nprocs_label"

text="No. of procs."

width="16" />

<aui:Label name="nprocs"

align="center"

width="8"

bold="true" />

<aui:Label name="cpu_label"

text="Total %CPU"

width="16" />

<aui:Label name="cpu"

align="right"

width="6"

bold="true" />

</aui:Box>

<aui:Box name="table_header" flow="h">

<aui:Label name="own"

text="PID"

align="right"

width="8"

bold="true"

reverse="true" />

<aui:Label name="proc_cpu"

text="%CPU"

align="center"

width="10"

bold="true"

reverse="true" />

<aui:Label name="cmdline"

text="COMMAND LINE"

bold="true"

reverse="true" />

</aui:Box>

<aui:ScrollView name="proc_view">

<aui:Table name="table" columns="3" />

</aui:ScrollView>

<aui:Label name="footer"

text="Press Q to exit."

align="center"

bold="true" />

</aui:Box>

</aui:Window>

<!-- Signal mappings -->

<aui:signal key="q" handler="on_quit" />

<aui:signal key="KEY_UP" handler="on_up" />

<aui:signal key="KEY_DOWN" handler="on_down" />

<aui:signal key="KEY_PPAGE" handler="on_pgup" />

<aui:signal key="KEY_NPAGE" handler="on_pgdown" />

<!-- Palette -->

<aui:palette>

<aui:color name="pid" fg="3" />

<aui:color name="opt" fg="4" />

<aui:color name="cmd" fg="10" />

<aui:color name="args" fg="246" />

</aui:palette>

</aui:MiniTop>

|

mini-top.xml

This is a slightly bigger XML document where we have a few more nested widgets,

as well as a new feature: the palette element. Let's start by looking at the

UI part. We see that the child of the Window element is now a Box with

vertical flow. This means that all the children that we add to this box will

span the whole width and pile up vertically. We use this element to divide the

window into three parts: the top one will hold some summary stats; the middle

will hold the process table; the bottom part is just a label telling us how to

quit the application.

We see that the top part is just another Box, this time with horizontal flow.

Inside we have four labels, two of which have fixed content and act as actual

labels, describing the values that we will update. In this case we will keep

track of the number of active process and the total CPU load.

The middle section of the UI is a ScrollView, which allows us create widgets

within it that overflow the actual terminal size. This is an abstraction that

makes for easy scrolling of overflowing content. In this example, inside the

ScrollView we have a Table object with three columns; these will be the

process ID, the CPU load for the process and its command line.

To make the UI appealing to the eye, we shall make use of colours, and this is

where the new palette element in the XML document steps in. This is used to

give a name to curses colour pairs. In this particular example we are changing

the foreground colour only, but in principle we could change the background as

well by setting the bg attribute. We'll see with the Python code below how to

easily reference the colours in the palette.

Before moving on though, I appreciate that there isn't much of an official

documentation of the UI framework used by the Austin TUI project, and this post

is a way to make up for that as much as possible for now. Looking at all the

sample XML above you might be wondering where all those attributes come from.

For example, when we look at a Label element, we see

<aui:Label name="label"

text="Hello World"

align="center" />

The attributes name, text and align are precisely the arguments of the

__init__ method of the Label class. Hence, if you want to find out which

attributes are available for a certain widget you will have to find it in the

widget collection and look at its constructor.

Every widget has at least the

nameattribute. Every other widget requires its own set of attributes.

Widgets are discovered by the view builder in a dynamic way, which means that

you could sub-class Widget and make your own widgets. If you do so and want

to reference your custom widget in the XML document, all you have to do is use

the class name as element name. For example, if you have something like

from austin_tui.widgets import Widget

class MyWidget(Widget):

def __init__(self, name, some_attribute):

super().__init__(name)

...

then in the XML document you would have something like

<aui:MyWidget name="mywidget_instance" some-attribute="42" >

<!-- any potential children here -->

</aui:MyWidget>

Updating the UI

For the model part of the MVC pattern we don't have much to say here as that

will depend upon your application. In this post I will show you how to make a

minimalist top application, so we can have a look what the model code could look

like in this case a move over to the more interesting bit, which is the C in

MVC.

import psutil

data = sorted(

[

(

p.info["pid"],

p.info["cpu_percent"],

p.info["cmdline"],

)

for p in psutil.process_iter(["pid", "cpu_percent", "cmdline"])

],

key=lambda x: x[1],

reverse=True,

)

If you are familiar with the psutil module, you will see that we are iterating

over all active processes to extract some information from them. In this case we

are interested in the PIDs, the CPU usage and the command line. These three

values will be used to fill in the three columns of the Table widgets that we

introduced in mini-top.xml. As we will see, there is some more code that we

could put into the model part of our design, but for simplicity we will embed

that into the controller. The code below shows you how to update the UI every 2

seconds with fresh system data.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 | import asyncio

import psutil

from austin_tui.view import View, ViewBuilder

def format_cmdline(cmdline):

if not cmdline:

return ""

cmd, *args = cmdline

args = " ".join(

[arg if arg.startswith("-") else f"<b><opt>{arg}</opt></b>" for arg in args]

)

return f"<cmd>{cmd}</cmd> <args>{args}</args>"

class MiniTop(View):

def on_quit(self, data=None):

raise KeyboardInterrupt("quit signal")

def on_pgdown(self, data=None):

self.proc_view.scroll_down(self.table.height - 1)

self.proc_view.refresh()

return False

def on_pgup(self, data=None):

self.proc_view.scroll_up(self.table.height - 1)

self.proc_view.refresh()

return False

def on_up(self, data=None):

self.proc_view.scroll_up()

self.proc_view.refresh()

return False

def on_down(self, data=None):

self.proc_view.scroll_down()

self.proc_view.refresh()

return False

async def update(self):

while True:

data = sorted(

[

(

p.info["pid"],

p.info["cpu_percent"],

format_cmdline(p.info["cmdline"]),

)

for p in psutil.process_iter(["pid", "cpu_percent", "cmdline"])

],

key=lambda x: x[1],

reverse=True,

)

self.table.set_data(

[

(

self.markup(f"<pid>{pid:8d}</pid>"),

self.markup(f"<b>{cpu:^10.2f}</b>"),

self.markup(format_cmdline(cmdline)),

)

for pid, cpu, cmdline in data

]

)

self.nprocs.set_text(str(len(data)))

self.cpu.set_text(f"{psutil.cpu_percent():3.2f}")

self.table.draw()

self.root_widget.refresh()

await asyncio.sleep(2)

def main():

with open("mini-top.austinui") as austinui:

view = ViewBuilder.from_stream(austinui)

view.open()

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

try:

loop.create_task(view.update())

loop.run_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

view.close()

print("Bye!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

There are quite a few new things that we need to explan here. First of all we

see that we implement MiniTop as a sub-class of View and we declare all the

required event handlers. We now have an update asynchronous method which we

use to update the UI every 2 seconds. For this to work, we need to create a task

using this method before starting the asyncio event loop (line 83). On line 43

we have the model logic that we just saw above and the interesting part starts

after that. On line 55 we set the collected tabular data to the table widget.

You would have guessed at this point that the way to reference a widget declared

by the XML document is via attribute access on the view object. In this case,

the Table element has the name attribute set to table. Therefore we can

reference it inside the MiniTop instance via self, i.e. self.table. On

lines 66-67 we do a similar thing, i.e. we update the value of the nprocs and

cpu labels with the number of process and the total CPU usage respectively. At

this point, no update is displayed on screen and this is for efficiency reasons.

Once we have modified all the widgets that needed to be updated we can force a

redraw by calling the draw method. This merely updates some buffers in memory,

so in order to flush the changes to screen we have to make a call to the

refresh method on a window-like object. In this case the simplest thing is to

just refresh the whole root widget (line 70).

You might have also noticed that most of the event handlers are explicitly

returning False. That's because we are manually forcing a refresh of the

ScrollView widget (lines 23, 28, 33, 38) and therefore we return False to

avoid propagating the refresh request further up the widget hierarchy for

performance. Here we only needed refreshing the ScrollView; we could have

omitted the manual refresh and returned True with the same result, but the

window that would get refreshed would be the root one.

Spicing Things up with Colours

The last thing we need to have a look at are those mysterious calls to the

markup method and the format_cmdline helper function. This is we we find

references to the palette element in the XML document. Let's have a closer

look at line 58 for example.

self.markup(f"<pid>{pid:8d}</pid>")

The markup method of a View object is a convenience method for creating

strings with multiple attributes, like foreground/background colour, boldface,

reversed, using an XML-like markup syntax. In this particular case, we want to

write the PID on screen using the color pair with name pid declared inside the

palette element of the XML document. On line 59 we use the <b> tag to make

the CPU usage bold. For the command line we do something more complex with the

format_cmdline function. If the command line is non-empty, we use the cmd

colour for the actual command, and the colour args for the rest of the

arguments, with the exception of option values, which are highlighted with the

colour opt and with boldface. This spares us from having to manually split a

string into chunks with different formatting.

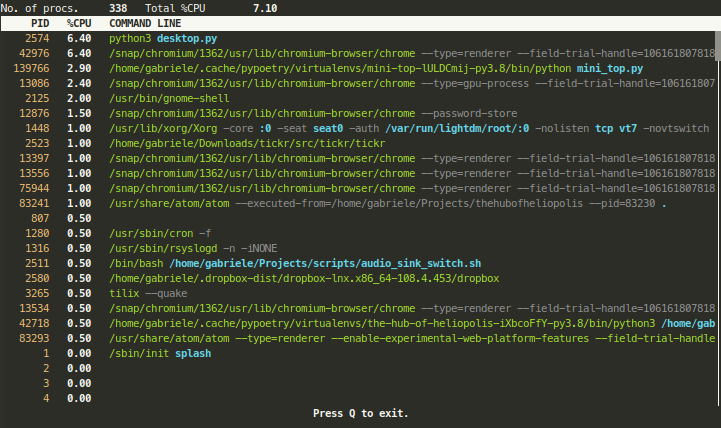

When you run the code above you should see something similar to the screenshot below appearing in your terminal.

To quit the application, simply press Q as suggested at the bottom.

You can find a working example of this minimalistic top utility on GitHub if you want to play around with it and familiarise a bit more with the Austin TUI way to resourceful text-based user interfaces.